-

Queercircle x Shadi Al-Atallah

In Conversation -

Ashley Joiner: So maybe we should start with your most recent show, I Lost the Title on the Plane. What was your starting point for the show and what was your process?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Basically, the starting point is being in a state of limbo. I was still in Bahrain when I was trying to plan it, but then my trip kept getting delayed. I last minuted everything, I wanted to work in Bahrain but my parents were moving house so I was basically staying with my girlfriend in her house. Didn't have anywhere to work. I was really stressing about it obviously. So the minute I got back, I had to phone up all, literally every studio provider in London and just be like, "Please give me a studio tomorrow. I just want to work." So I got the space that I'm in now, which is in The Hive with Koppel Projects and I bought rolls of canvas and paint from Atlantis and laid it out and started painting, not knowing what I'm going to do. I had no plans whatsoever.

I thought of a title on the plane and then I lost it and I kept messaging Ellie from Guts Gallery, "Please just give me some time. I'm just trying to remember it because it was a really, really, really good title." And I guess I took advantage of the position that I was in, where I didn't know exactly what I was going to do. So I decided to explore this idea of not knowing and transitioning or feeling stagnant.

The main idea that I was looking at was stagnation in swamps, things that are necessary and breed life, but they're kind of seen as, I don't know, inconvenient. Because there was a swamp in Bahrain, one of the few swamps. And now they've released some article saying, oh yeah, we're going to actually cultivate more swamps in Bahrain because they're actually good for the environment. But the swamp is so beautiful. But it's also so littered, so untaken care of, just neglected basically. And it was the only source of nature that I had access to because I like to go to nature to feel calm and I didn't have that space when I was there. So I would just sit near this littered swamp with my dog, taking her own walks there.

And I began contemplating this idea of stagnation. I felt stagnant, creatively, emotionally, in so many ways, but I was trying to view in a positive way I guess, the same way a swamp is just stagnant water. You can bring life out of it. So I was trying to bring life out of a kind of situation that wasn't great,it wasn't the best situation to be creative in. So I was exploring that emotion and that's what I was painting. When I was painting, I was thinking of that experience and those feelings.

-

-

Ashley Joiner: I think that was like such a common experience for so many people. With the uncertainty of Brexit, lockdown restrictions, travel restrictions, a lot of people were trapped, unable to move in places that weren't necessarily home, so many queer people that were trapped in homes that were homophobic or unsafe, especially young people.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Exactly. And I think queer people and disabled people were disproportionately affected by this kind of state of not knowing what's going to happen.

Ashley Joiner: Is it fair to say painting is a cathartic moment or process for you?

Shadi Al-Atallah: I think that's how it started. And I go through waves, I guess, of how I view painting. Sometimes it feels like a necessity just to survive. And sometimes it feels like it's something I'm genuinely doing to understand how I'm feeling in the moment. So I think it would be unfair to say that my relationship with painting is consistent because it's not. I went through so many periods of hating the idea of painting because it just felt like something I wanted myself to do, but I couldn't bring myself to do. So it's this fluctuating relationship, but when I do it and I do it out of genuinely just needing to express myself, then it's definitely a cathartic experience.

Ashley Joiner: Have you found that that has changed since you've graduated? Is there a different kind of pressure?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah, I think it's become better because I stopped viewing painting in an academic sense now. Now there's no pressure to paint for tutorials or meet a deadline like that. I mean there's obviously deadlines for shows and things, but it's more open. I don't know. I mean I liked my experience at the RCA when it was face to face and then when it became online, it just didn't feel real. I didn't have a studio space, but I was still attending tutorials. So it was a bit, it was just odd.

You didn't have much to offer, but you were still, you had to pay for the education that you weren't receiving. But I think it's improved a lot since I've graduated. I feel that pressure lifted off a little bit. I feel like I can breathe and when I breathe, I paint better. And I'm a bit more experimental. I'm not worried about making large scale pieces. I've been looking at painting on paper a lot and I've liked it. I don't know why I felt pressured to paint so large scale, but with the pandemic and lack of space, I've actually grown to like paper and just working on a smaller scale and taking a bit more time to do things.

-

-

Ashley Joiner: Is breathing a part of your coping strategy for mental health and physical health?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah, definitely. Definitely. So I was actually, one of the things I was thinking about when I was reading the questions you sent me was this whole, I guess relationship between mental health and my work, because I always view it as a subconscious link, not an obvious link. I'm not researching mental health. I'm actually researching other things like cathartic practices and ways that people in different cultures express their feelings using the physicality of emotional states. It's something that I'm really interested in. Emotion doesn't just live somewhere in your head. It's not just thoughts and feelings. It's so much more about the body. So two years ago, I got an autism diagnosis and that was a huge part of me trying to understand why I always struggled with understanding emotion within myself and others, but also why I prefer thinking of the physicality of emotional states.

I wasn't always good with facial expressions or understanding them in other people. So I just researched them. I was like, what does it mean when someone does this? Which I would literally just research or ask people on forums, what does it mean? And I got obsessed with it. And it was unhealthy to try and read too much into other people. My mom is really analytic as a person too. So she would just sit and analyze people's body language. And I was surrounded by this fascination with body language and then it transitioned to me being fascinated with dance and all these expressions that don't require the burden of language.

Ashley Joiner: Have you read a book called The Body Keeps The Score?

Shadi Al-Atallah: No, that's one book that's been on my list.

Ashley Joiner: It’s this idea that emotion actually lives in a physical form within our body and makes us do certain things and trauma is such a big thing.I think for me with my own mental health, it helps to give it a physicality, recognising that it exists and respecting it, I guess.I was on a panel the other day where they asked me how I look after my own mental health and I had a little, I'm not sure if you would call it a breakdown or a breakthrough in front of this live audience.I ended up pouring my heart out in front of this live audience. And it felt very vulnerable at the time.Then all of a sudden, people in the audience started sharing their own experiences. Your work almost gives people permission also to open up and talk about their own experiences.

When making your work, you said it's kind of a subconscious thing about mental health, but does this role of community wellbeing, the mental health of people within the LGBTQ+ community, does that play a role in it or is it all very much from a personal?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yes, it definitely is a motivator. I would say it's not directly related to my process. But when I go to my shows and I speak to some people in the group shows that I have been in, also in some of my solo shows, the way that people respond to my work, I guess it makes me feel like it has a purpose beyond just what I'm doing immediately as I'm painting it. So, yeah, I definitely connect with that. I do love the way that people interact with my work. That's a huge part of it. I think in my first show I've had people posing in front of my paintings or just physically trying to contort in the way that the bodies and the paintings do. So I do love that. I think that some of the vulnerability in the work does allow people to think about their emotions. I hope it does.

-

-

Ashley Joiner: As a viewer, I can say it did me. Just going back to what you just said about dance like forms and removing the need for language. I read somewhere that at one point in your childhood, you were mute?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah. I was selectively mute, so I was mute in certain situations, especially school, with certain members of my dad's family. It was never my mom's family, just my dad's family. Yeah, I struggled to connect with people in school. I didn't know why. My teachers would tell my mom, she's a good student, but we've never heard her voice before. My mom started taking me to all these... She thought it was a self confidence issue so she started taking me to this life coach. I was eight, I didn't need a life coach, and she [the life coach] would tell me "Oh, you could just walk up to people and introduce yourself." I couldn't speak to her because she was a stranger so I was just mute throughout all the sessions that my mom took me to.

It just felt like a lump in my throat and that lump just kept growing and growing. Then I discovered writing. When I was 11, I was writing the cheesiest love poetry, just trying to understand my sexuality at the time too because I had my first crush when I was 11. So I was discovering that I was gay and I was writing. I was on all these websites where you can submit your poetry and everything.

So writing became my first form of speaking in a way, to strangers on the internet. It felt freeing. And then I lost my relationship with writing. I forgot how to write. I started becoming a little bit more vocal, so I developed friendships and I think when you do that and you get out of your own bubble, you can forget the creative parts of you. That’s when I rediscovered paint, I mean I discovered painting when I was 14. I moved to Bahrain to study and that was the first time I was exposed to any type of art. I didn't grow up around art. Figurative art was banned in Saudi. It was religiously and politically banned like no figurative depictions. Yeah. So when I discovered figurative art, that's whenI realised that I could paint people.

And something about it, just the fact that I didn’t do it when I was younger, not in school or anything, it just felt like a thrill somehow, just to paint a face or a body. And that's when it became my language of expressing myself. I had a teacher who encouraged me a lot and that was when I took on painting as my main creative language. So there's a huge relationship between those mute days and painting because it felt like a journey to try and find a language that I felt most comfortable speaking in.

Ashley Joiner: I always talk about mental health as like a journey, so one day is very different to the next. When you look at your works collectively, you are able to see this change state. We might not necessarily recognise what those different states are, but we can see that there is a variance between just based on the position or the shape of the body.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah. I think it's interesting to look at my work on a timeline. I don't do that enough. I'm the type that’s just ‘get it out of my face. I never want to look at it again.’

Ashley Joiner:I wonder if there's something in that, not lingering on the state of that day.

Shadi Al-Atallah Yeah. I guess it's kind of like writing something on a note and burning it.

Ashley Joiner: Because you work quite quickly, don't you?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah. I work really quickly.

Ashley Joiner:Right. And I guess that's also part of it, right? If you was to linger on a painting that you would be covering so many days and your state of being varying so differently.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah. I've done that a few times. So I’ve started paintings and then ran out of time, the studio has to shut or something and came back to it two days later because I wasn't motivated to go the next day. And I actually completely forget what even started this painting. And it always ends up really badly because I don't even remember where this painting came from so I overwork it and it turns out to be my worst painting. It needs to be immediate or else it's not going to be good. And it's annoying because I have to work in bursts and then burnout in between. But that's just how I paint. And there's no other way that I feel satisfied with the painting.

-

-

Ashley Joiner: It's interesting to hear that you're working on smaller paper now because when we first met at one of our “think-ins” about what Queercircle could and should be, you were talking about the possibility of a larger space to be creating larger works. Are the smaller pieces a response to conditions at the time?

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah.

Ashley Joiner: Do you approach these different scales in different ways? Are you dealing with different issues, topics?

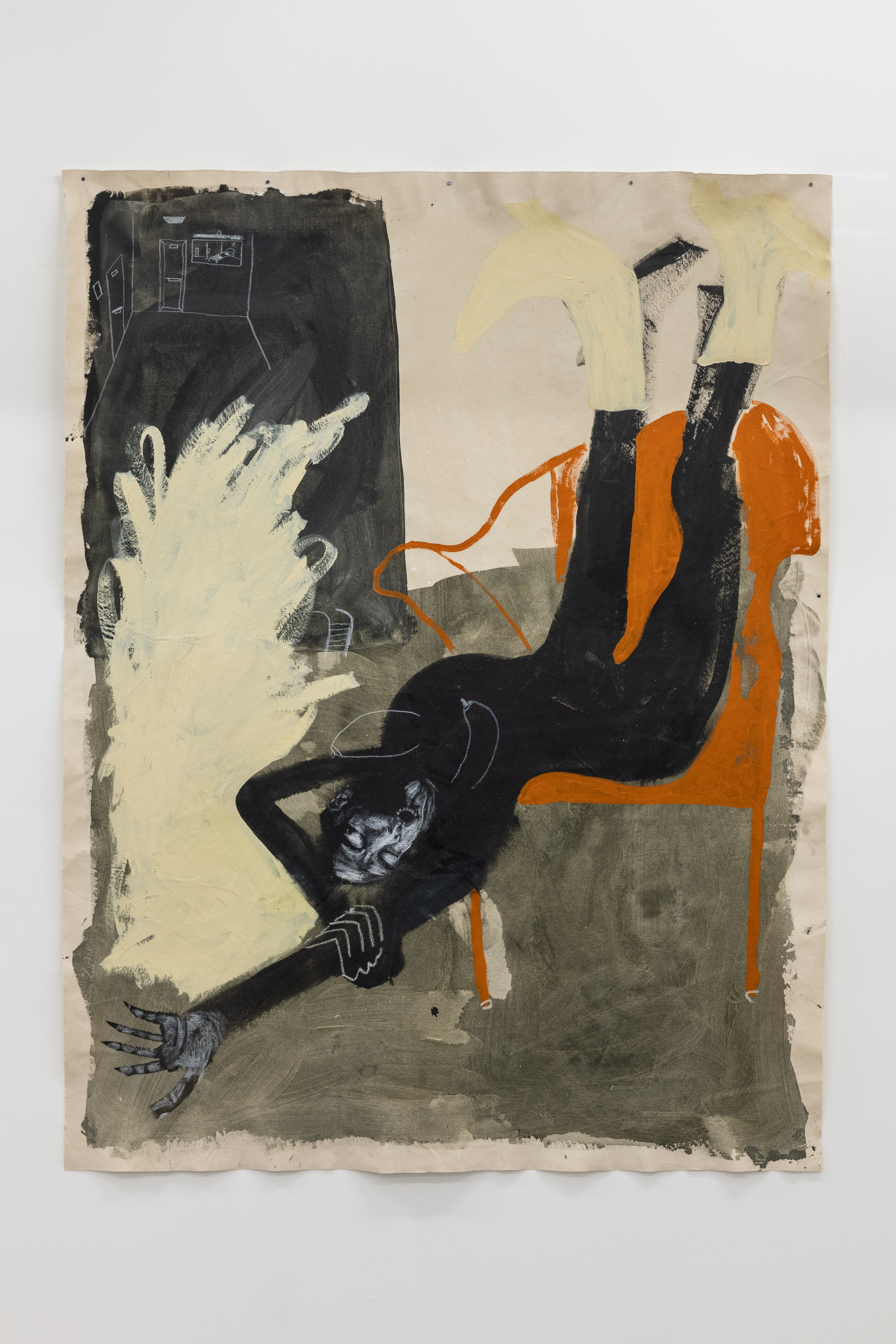

Shadi Al-Atallah: I think the larger paintings are always more satisfying to look at because I build it up not knowing what it's going to look like at all in the end, because it's just bigger than me. And I have to work around it, especially if it's on the floor, then I really don't know what I'm doing because I'm painting upside down or from different angles and I'm just walking around it. But with the paper works, I just feel they end up looking, I guess, more refined. So aesthetically, they look more satisfying, but maybe personally not.

I think there's pros and cons of me going either route I guess, but I'm still painting large scales and that's my main form of painting, but I used to have this aversion to painting small scale and I'm working on this relationship. With small scale work, I get a more immediate result. I can just paint it really quickly and end up with a painting as opposed to the large scale ones where I have to wait hours for layers and layers to dry and then I see the end results. So yeah, I think the small ones I've realized they just give me a burst of, serotonin or something. I just see it and I'm like, yeah, it's done. I just painted something in half an hour.

Ashley Joiner:And the larger pieces you mentioned about not knowing what's going to happen until everything's dry. They're so rich with textures and materials. Can you talk a little bit about the materiality of your work?

Shadi Al-Atallah: So maybe I could start with the canvas because that's one of the main components of my work. So the canvas is unstretched because it’s related to the immediacy of what I'm doing. It feels like whatever I've just painted should just be put up on the wall exactly as I made it. It's actually part of my way of combating this fear of my work being unfinished and it's also a way to stop myself from over refining my work.

So that was one of my main downfalls when I first started painting is overworking something or underworking something. It never feels right, never feels finished. So to abandon it and just put it the way it is, It just feels right.

The way I paint is I mix up a lot of really liquid, fluid paints. Especially the black that's usually bubbling as the background of my painting. It's the first layer I put on. So I'll spill a lot of ink mixed with acrylic and Diet Coke to create this bubble kind of effect. And then I mix up thicker paints and I like feeling the paint. Sometimes I rub it in with my hands, if the brush isn't doing a good enough job. So I like interacting physically with the paint onto the canvas.

When I first started I was painting straight lines and in more of a, let's paint in this box type of way, but now I feel more free and I'm using larger brushes and it’s a lot quicker. I like the liquid nature of the paints that I use, the way I can just layer them on. And then it looks like abstract shapes and then I'll get the chalk, pencils and crayons that I use and I work on top of it. It just feels like the painting is coming to life.

It's an accumulation of so many years of trying so many things and that's what I ended up with right now. But I always like to switch things up. So a lot of my paintings don't look completely cohesive in technique, but I like it that way. Whatever feels right in the moment does.

-

-

Ashley Joiner:I think that whether we're exploring our gender or our sexuality or our mental health, or da, da, da, da, da, this idea that things change on a daily basis, and that what you are painting with, or how you painting would change from day to day, makes sense.I like that you mix Diet Coke with your paint. How did that happen first of all?

Shadi Al-Atallah: I had a Diet Coke addiction, so I ran out water and medium and everything. I was kind of broke too. So I was just like, I'm not going to go and buy 60 pound bottle of medium. So let me just pour some Coke and it actually ended up looking really, really cool. So it's now a part of my process. It bubbles it and carbonates the paint.

I don't know does it ruin the paint? Does it peel it off in the future? I don't think it does though. I mean, I tried to research it after because I was worried. I was like does this affect how stable my painting is? Imagine it just peeling off?

Ashley Joiner: They only last for five years, that's it. But maybe that's part of it too, if that does happen, kind of embracing that unfinished.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Imagine.

Ashley Joiner:Maybe you're embracing this unfinished process and even when you're finished painting, they're still not finished and then they're going to evolve.

Shadi Al-Atallah: It just self-destructs.

Ashley Joiner: Yeah. Self destruct, evolve, depends how you look at it. I like that. Maybe we should revisit in five years. We'll do some check-ins later on.

Shadi Al-Atallah: We should.

Ashley Joiner:Speaking of embracing the unfinished and identity as a process, you have a particular approach to self-portraiture. Can you talk more to that?

Shadi Al-Atallah: I've spoken to a few people and they're confused about the self-portraiture aspect of my work, because it's not exactly self-portraits of me. I'm not painting different images of myself. I wanted to talk about my journey to self portraiture. I was doing illustration and I hated it. It was summer 2017, In frustration, I just got this big piece of canvas and I was trying to paint how I feel and I ended up painting myself surrounded by flowers with a chilli plant in the back. 6 Red Chillies is the tile and it came from this recipe for healing from betrayal, 6 red chillies are one of the ingredients for the spell. I was so desperately trying to heal myself in the state of emotion, but I never ended up performing the spell. The painting process was actually more healing.

I was really interested in Frida Kahlo’s work at the time too, so Frida Kahlo's self portraits were, I guess the main inspiration that drove me to go down that route. I know that she was exploring her chronic illness and I was having health issues at the time too. So I was like, let me paint myself, but I've always been camera shy. I just got pictures that I found online and tried to make a Frankenstein's monster thing out of all the images and it felt like me.

That's been my process since then is go online, find memes, take screenshots of some TikTok or YouTube videos or just pictures that I feel like, oh, you know when you just see something and you're like that feels right to me in this moment?

I compile all of these and some porn stills and images and just things that are everything at once, that could be representing what I'm feeling. And then I'll sometimes collage it on my iPad. So I'll actually build it up digitally and then use that as my main reference point.

Sometimes I'll just have all these images open up on my laptop and I'll take components of them, cut them out in my head and put them down on canvas. So that's where my interest in self-portraiture comes from.

-

-

Ashley Joiner: I guess also seeing yourself in a culture that was not always available, right? So we make ourselves, we build ourselves with tiny little composites.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah. And I think it keeps my work not the same. It's not all like exactly me. Every time it's a different person that's me. I like this idea of connection with people because we tend to go deep in our heads, sometimes we think we're the only ones that exist. We're the only ones that feel that way or, especially when you feel so shit and you think no one has ever felt that shit before except for you.

But then when you zoom out of it a little bit, your emotions are other people's emotions and there's a sense of connectivity that I like to explore. So I think all these people that I don't know are me in that moment and they don't know it. Yeah, that's it.

Ashley Joiner:Well, I'd like to see those collages at some point, if you're willing to.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Oh, yeah. I can send them.

Ashley Joiner:So, queerness is obviously at the forefront of your work.And you mentioned previously that there was no art growing up. Was there any kind of queer representation? Did you have anyone to look up to? What was the experience growing up queer?

Shadi Al-Atallah: The only exposure I had to queerness was negative exposure. We had leaflets given out to us in school or religious lessons being like, you're going to burn in hell basically. When I was young, when I thought of queerness I thought of hell, which is not a great thing. And then when I grew up, I actually came to like hell, hellish imagery. I think it's interesting. And I love, obviously I obsessively watched like Lil Nas X's music video with hell and I loved it. I think I was scared of hell when I was young, but growing up I became drawn to darker imagery.

I think it's a really good way to deviate from the religious norm in a really confrontational way. And I like confrontational things that are not centering hetero gaze. They're not exactly addressing heterosexuality as the norm, by presenting imagery that is so feared and hated by people who use religion as a tool to oppress LGBTQ people. I was drawn to that. When it comes to my sexuality/gender, I liked the way people got pissed off when they saw me out in public, I got a bit of a thrill out of it. I don't know why. I think It's a coping mechanism, but if you view it as like a middle finger to bigoted people, then it's a bit of an easier way to cope than I guess, than to go back home and cry about it, I can laugh at it instead.

I did have friends that were queer. I went to an all girls school.

And that's where a lot of homosexuality occurs usually. It's the perfect environment. There were a few girls older than me that looked up to who were presenting in a more masculine way. I did it, got almost kicked out of school and that's why I went to Bahrain. So I guess my whole experience growing up was always revolving around my sexuality. Moving countries, moving schools, moving friendships was all centered around my gender identity and sexuality. So it's inevitable that my work will, I guess, center it too. Because a lot of my life changes were influenced by how people viewed or reacted to my sexuality.

So many of my experiences were a product of that. And I guess, because I grew up having to censor my sexuality and gender, because that was the only thing that people saw when they looked at me because I've always presented more masculine. So I was visibly queer to people. In my paintings I try and make the figures ambiguous or visibly queer just to force that representation in figurative painting.

-

-

Ashley Joiner:Definitely. And I mean, it's funny that you say you were tapping into these dark references and stuff because there is an element of that to the figure at times.The torso in some ways is taking over this quite recognisable domestic setting for instance. And there is an element of ambiguity and anonymity to the figure.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Yeah, definitely. I think I like the way that it doesn't... I try to purposely not shy away from, I don't want to present queerness as ‘good’, good as in angelic or good as in rainbows and butterflies. It doesn't have to be good in that way. It can just be good because it's real and it's human and you go through all the kinds of emotional states that any other human goes through. So I like to view queerness in a human lens and I think we're often dehumanized. So just saying I'm queer but I'm also experiencing grief that has nothing to do with my queerness or trauma that has nothing to do with my queerness. This is what being queer is about. It's just about being human and also you just happen to be queer. So I think that's what I like to think about.

And so I mix in these poses from traditional dances that are performed in Zar rituals by African diasporic communities in Saudi. And they're a way of being possessed by spirits or the devil and the dancing is usually around a fire, it’s mainly a male dominated practice really. It's not done by women. It's done by women in a different way, but not in a really physical way, because women are not expected to do things that are too physical. So I think by combining these two, the culture that would never accept the queerness and then this queerness that the only representations of that I had growing up were the L Word and I don't know, Elton John, nothing related to my culture. It feels good to be able to combine them in a way that feels right for me. And maybe these two things were never meant to be brought together, but it feels good to bring them together.

Ashley Joiner: The dance that you mentioned. Is it like a cleansing ritual?

Shadi Al-Atallah: So the spiritual origins of this dance have been wiped away with the... In the seventies and eighties, when the new religious norm became extremist, all the spiritual significance of a lot of practices were erased.

I think it was a way for people to connect with their ancestors. It has links to similar dances still done right now in parts of East Africa and they've also had their own fair share of Abrahamic religions coming and taking away the spiritual components of them. But I think a lot of them are, I guess, purification rituals or ways to connect with ancestors. That's how I like to view anyway, a way to connect with the spirits of your ancestors. Growing up your ancestry is so important. In Saudi culture, your ancestry is one of the main components people are divided into tribal and non-tribal. If you're non-tribal, you're ancestors can't be traced, which basically means either you had previously enslaved ancestors or you were you were just kicked out of a clan or something. So you're devious somehow.

I guess these practices that try and reconnect you to your ancestors who you don't even know, I think there's something profound in that because it's like screaming into the sky and not knowing who's going to answer. But I'm not a spiritual, I am a spiritual person, but I'm not, but I think that kind of practice is important to me is to connect with something, even if it's not God, if it's just my ancestors or spirits.

Ashley Joiner: Yeah. I guess there's an element of that within queer lineage too, right? We don't necessarily know our ancestors, the lines are broken.

Shadi Al-Atallah: Exactly right, yeah.

Ashley Joiner: But there was an element of wanting to connect to something. I mean your paintings are quite performative, but have you explored performance as a medium?

Shadi Al-Atallah: This is something I've been looking at for the past three years and it's something I have this weird fear of. I used to do a lot of drama in school and everything. So performance wasn't something that was foreign to me. But since I moved to the UK, I felt more afraid of going down that route, but it's something I'm exploring. I've written down a few ideas and I'm just looking at ways to implement them. I've been thinking about sound a lot more. So thinking of how sound connects to the spiritual aspect of my work because sometimes imagery just doesn't do it. So that's my next step.

Ashley Joiner:

And are you working towards anything now?

Shadi Al-Atallah

Working towards anything specific? Not really. Not really. No, I'm just trying to use this time to just paint and focus on expanding my practice. It's not something I was able to do for the last few years. So it's good to just feel like, okay, I could just go to the studio and there's no pressure to do anything specific, to just see where it takes me.

-