-

Jakob Rowlinson & Rebecca Jagoe

In Conversation -

-

-

-

When I was at the RCA, I had stopped making work for a while, I was only writing, and then I applied to the sculpture course to reengage with a material practice that I felt disconnected from. I became very reverential around ideas of making things properly, and using materials which would last into perpetuity. It’s weird trying to make sure your work outlives you. A sympathetic read of this would be the idea of creating objects of cultural value, but a perhaps more realistic, or cynical read, is that it’s just a capitalist market-driven mindset whereby the collectibility of your work is contingent on it being able to last a long time without massive intervention. I don’t think any of us wake up every day and actively choose this mindset: I think it’s a more pervasive one which permeates a lot of institutions, and manifests in a focus on using the ‘correct’ materials ‘correctly’. A huge influence on my thinking has been Caroline Walker Bynum’s writing on materiality in high Medieval Catholic culture. In particular, she writes ‘The problem for medieval worshippers and theorists, both those who doubted and those who believed, was change – not the line between person and thing, or the line between life and death, but the divide between what something is (its identity) and its inevitable progression toward corruption.’ This divide, the Heraclitus vs Parmenides, Being vs Becoming question, is one that constantly comes up in my thinking. At its heart is the question of if something changes significantly, does that make it ontologically a different thing from the thing it started out as. Under Western taxonomic language, arguably, it does, but I want to push back against this idea that change is corruptive, and that artworks must remain unchanged into eternity. My works will have a lifespan, a lifespan that I cannot control.

-

When it comes to queerness, I think questions of the lifespan and futurity of my works, alongside questions of conclusiveness, are embedded in this. I don’t necessarily ascribe to the queer negativity school of thought wholesale, but I do think that a huge part of queerness (a socialist queerness that does not assimilate into existing capitalist patriarchy) is a refusal of these taxonomic and totalising ideas of language, ideas which might not allow for the possibility of change. Mel Y Chen talks about this wonderfully: as overused as it has become, ‘queer’ is not a word with a clear centre and periphery. It does not have a delimiting set of attributes. ‘Queer’, when it is not being coopted by multivitamin companies, or even the fucking armed forces, should be able to offer an ability to refuse legibility. And so tied into this is idea of refusing to be understood, is the possibility of mutability and change. And so, this is a loooong and roundabout way of saying, that I think once I let go of the idea of making works which had to somehow stay the same into eternity, to be visibly and fixedly one thing, and to be objective commentary on a topic, I also allowed a material queerness to enter into my work, from the objects I make to the performances I write. This is not to say that all work which is changeable or mutable is therefore inherently queer. Rather, what I mean is that making work that is focussed upon conservation, and remaining unchanged into eternity, and therefore has a fixity to it, is materially antithetical to how many, myself included, would understand the term ‘queer’ to exist linguistically and politically.

So anyway. All of this tangent is to say, I think it took me a little while to start to examine and unpick this tendency in myself, and when I made Balmainimal, I sort of had this ‘huh’ moment. But you know, when I’m not wearing it, I still haven’t resolved the best way to display it. And it’s slowly disintegrating, and I like that. It can’t really be worn anymore, it’s too fragile. A while ago it was being eaten by moths. I wasn’t thrilled about it, but I don’t know, it’s also the nature of using certain biological materials (in this case shed snakeskins and hog hair). And this change doesn’t make it a diminished version of the work when it was freshly made. I’ve aged, the work has aged.

-

-

-

RJ: The reasons why my work brings in animal references, or any kind of other-than-human, as with yourself, varies from piece to piece, and also, as with yourself, is often related to the specific cultural narratives attached to that animal. Overall, I am really invested in dismantling an idea endemic to Western culture of human dominion over the earth. The Christian idea of the Great Chain of Being creates a very clearly demarcated hierarchy of humans above other-than-human life, and purports that only humans have souls. This idea allows the possibility of creating a very specific idea of who counts as human, and who does not. As such, it becomes possible to exclude certain groups of people from the category of human, and therefore remove or not recognise their agency, both culturally and legally. This rhetorical tool was necessary to justify many of the violences of capitalism, from extractive industry, to violent colonial practices, to enslavement. It was also used to justify abuses and restrictions enacted upon disabled people. Within my practice itself, it would be wildly inappropriate for me to talk about dehumanisation of majority ethnic people, but it is important to address within these sorts of research-led discussions, as the Western construction of the human is inextricably tied to the colonial agenda. In my own work, I approach the question of who is considered ‘human’ from the lens of disability. I was talking about this recently on a panel discussion, but on the top of my autism diagnosis it reads ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder (formerly known as Aspergers)’. Directly written into the history of that term, Aspergers, is the question of who gets to live and who gets to die. Hans Asperger determined that some children with ‘childhood schizophrenia’ (then the term for what is now called autism) had skills that could be valuable for the fascist state, while other disabled children were killed. This is the origins of the diagnosis ‘Aspergers’, and archaic ‘functioning’ labels (which unfortunately were not chucked out by the DSM because they are embedded into capitalist notions of productivity as a yardstick, but because they were just shown to be useless, as autistic people’s difficulties tend to be varied). So always, within conversations around disability and dehumanisation more broadly, loom the spectres of animality and monstrosity. These two spectres are themes that I constantly explore and return to, trying to collapse distinctions and separations between human and animal, human and ‘monster’.

-

But I also want to shy away from using this spectral idea of ‘nature’ as something which a) is intrinsically apart from the human, and also b) should some how be used as a yardstick (and a weapon) for what is or isn’t ‘natural’ human behaviour. As Lorraine Daston asks,

'Why do human beings, in many different cultures and epochs, pervasively and persistently, look to nature as a source of norms for human conduct? Why should nature be made to serve as a gigantic echo chamber for the moral orders that humans make?’

I wrote so much more about this, but in order to fully explore how this intersects with transphobic and queerphobic arguments I think I would need to write an entire book.

-

-

-

RJ: Yes indeed, this is a huge thing for me. One of the most formative recent experiences I had was going to the Bath Fashion Museum to see some of the glove collection of the Worshipful Glovers, where I was looking at gloves from the 16th to the 19th century. The ones from the Early Modern period were so incredibly captivating as objects, far more so than the Victorian ones. The 16th century ones were incredibly detailed and finely crafted, and the embroidery was so fine, but they were not perfectly symmetrical: they were very clearly hand-sewn, and the skill and meticulousness didn’t strive towards rigidity or regularity. In comparison, the later gloves felt soulless. Similarly, when I make work with a sewing machine, I never feel as proximate to it. Spending a long time over a very small patch of fabric, it feels like I know the work inside and out, I feel a level of intense connection to it that I can’t feel with works that I have made more quickly.

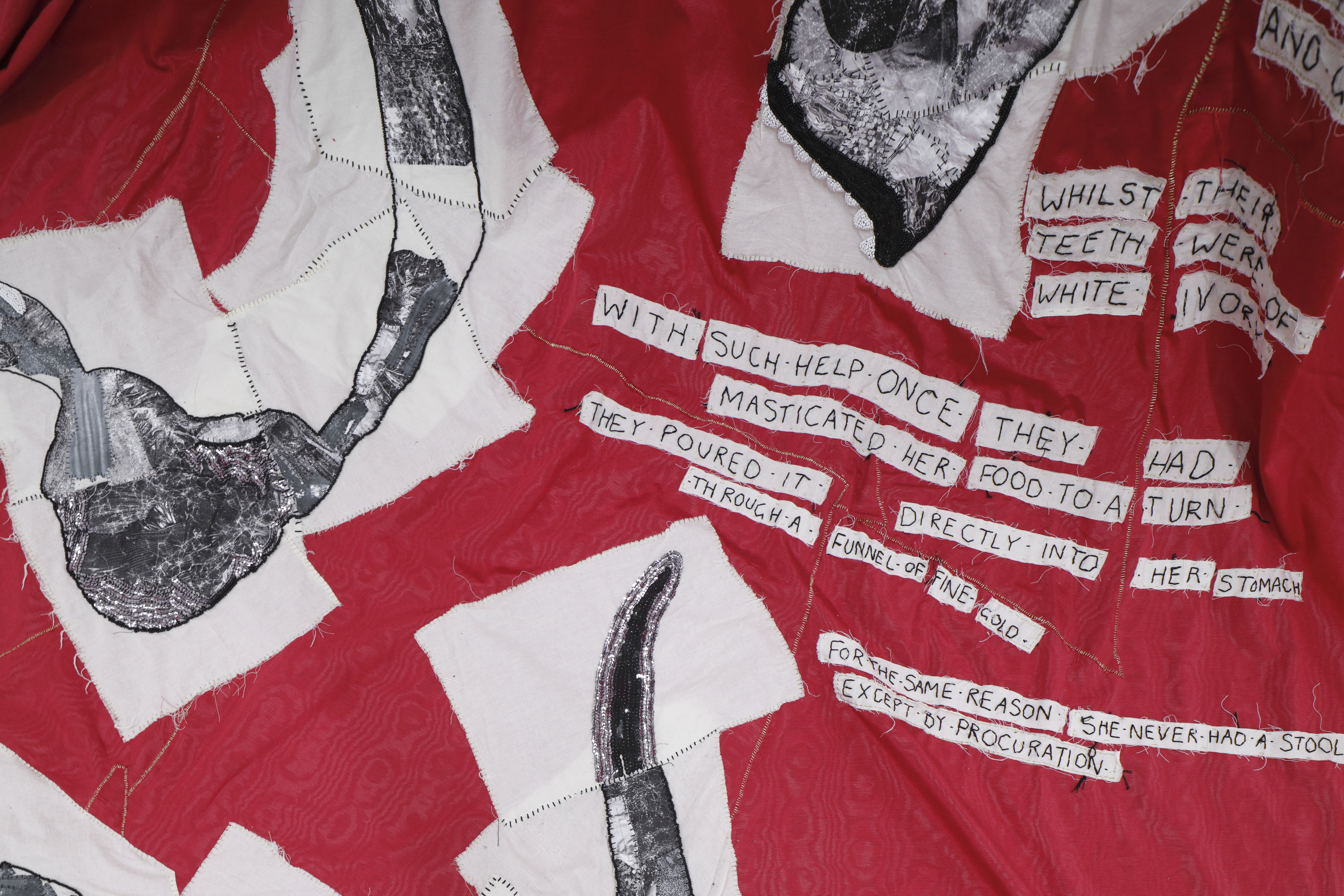

In my ongoing exploration of ideas of luxury and class association, unlike most luxury materials or embellishments, embroidery is literally a show of luxury through the labour of other people. In my own work, I tend to be more interested in embroidery not as a commodity, but as a catharsis, particularly the practices of sick and crip people. Another incredible archive I was blessed to visit (in a research group I co-organised with Jupiter Woods and Daniella Valz Gen) was to see the Lorina Bulwer embroidered letters in Norwich Castle Museum. Bulwer’s mother was her primary carer, and once her mother died, Lorina was put in the ‘lunatic’ section of Great Yarmouth Workhouse, until her death. While there, she made these very, very long letters on scraps of fabric sewn together, which read as stream-of-consciousness texts. The level of hapticity and proximity, and blunt humour, felt so much more present than the rigid samplers which were being produced by most embroiderers at the time. So I think I like to spend so long because I feel like I charge the work with a sort of presence that does not feel there when I use a machine. Because I am always trying to unlearn the most minor criticism I have received, I have to tell myself that while I want my work to be layered with detail, precision and perfection is not what I am striving for.

-

In a small way, I want to think through as well a relationship to object-making at an ambivalent time in capitalist production and increasingly mainstream environmental conversations. I remember once hearing that it was not uncommon for people to leave each other silk stockings in their will. I am really invested in the European medieval cosmology of objecthood, whereby everything holds a potency, potentiality and agency. Also, it is harder to find moments of visual intensity when surrounded by a surfeit of just, stuff. I think it’s why huge art fairs can be so soul destroying, because it becomes a one-upmanship of spectacle rather than offering an ability to focus with intensity on one thing. So, if it is not too grandiose to say, it’s perhaps a form of secular devotional practice, to spend this amount of time on one object, one stupid embroidered rock hat.

Sometimes I'm in awe of how articulate you are at discussing identity and queerness. I want to be more clear in speaking about certain things, especially to family and friends, but my tongue just sticks to the roof of my mouth. I'm often worried that if I haven't read a particular book or a particular author who address these issues, then I will look stupid. How do you navigate these things so (apparently) easily?

-